Reactive Programming with RxJS

Overview

In this blog we will dive into the world of reactive programming with JavaScript. We will go through these topics:

-

JavaScript basics

-

What is Reactive Programming?

-

Reactive Programming in JavaScript

So let’s get started!

1. JavaScript basics

First of all, let’s do a short recap on javascript. Programming for the Web javascript is the programming language of your choice. Together with HTML and CSS you are ready to become an web developer. Javascript offers even more with node.js the world of server-side development is your’s as well. Brendan Eich invented Javascript back in 1995. Two years after that it became an ECMA standard (“ECMA-262) .

First steps: Variables and Contants

Variables in Javascript are declared by “var”. With ES6 came ‘let’ and ‘const’. These are scoped to their running execution context. A variable declared with ‘var’ might be used by other functions as they are global when declared outside any function. ‘Let’ on the other hand is only approachable within their context of definition, so called block scoped. Quick example:

- Variables

var newString = "String"; let a, b = 10; let c = 10, d = "String"; - Constants

const newConstant = 10;

Moving on to: Arrays and Objects

- Objects

var myObject = { Name : "Max", Nachname : "Mustermann" Address : {Street : "Musterstraße", No : 5, ZIPCode : "11111" , City : "Musterstadt"} } - Arrays

var myElements = [ 2 , 3, 4, 5 ]; var myElements = new Array(2 , 3, 4, 5); var alsoMyElements = [ 2, "Hello", new Date(), 5 ];

We already looked at Variables, now Objects are like Variables since they are containers for data too. Objects can hold many values. Those values don’t have to be of the same type. Arrays are special variables too. They can contain many values as well. How to access those values? With objects you use the names of the values, e.g. myObject.Name returns “Max”. Arrays returns values by numbers, e.g. myElements[1] returns 2. Remember, the first element of an Array is called by 0, the second by 1 and so on.

Next on the agenda are functions. Functions are blocks of code, defined to fulfil a specific task. They are defined by the keyword function and a name, following parentheses, which can contain parameters. A function is executed when something, e.g. an event or even another function, calls is.

Here some examples:

function myObjectFunction (firstname, surname){

return { Firstname : firstname, Surname : surname};

}

var mySecondObjectFunction = function (firstname, surname){

return { Firstname : firstname, Surname : surname};

};

function myFunction (firstname, surname){

var name = myObjectFunction(firstname, surname);

return name;

}

The first function gets two parameters and returns them as object. As soon as the surrounding function or script is executed - the first function can be executed. The second function on the other hand is a functional expression and is ready to be executed as soon as the line, in which it is defined, is reached in the executed script.

There are some global functions you can use.

| name | example |

|---|---|

| eval | eval("3+2*4") // 11 |

| isNaN(Value) | isNaN("TRUE") // true || isNaN(8) // false |

| Number(object) | Number("354646.55") // 354646.55 |

| String(Object) | String(354646.55) // "354646.55" |

| parseFloat(String) | parseFloat("33.33333333") // 33.33333333 |

| parseInt(String) | parseInt(“456.235665”) // 456 |

You can use those functions with all JavaScript objects. Here is a list of all global functions.

event handling

As mentioned earlier JavaScript is the programming language of the web, so what’s more common in the web then to click on something or to input data? That’s why we’ll take a look at event handling.

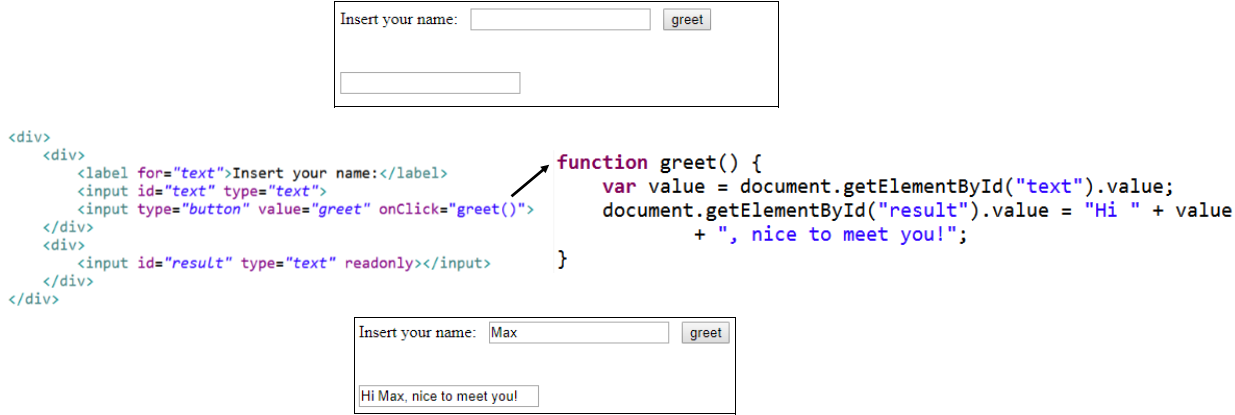

This is an easy example. We have a simple HTML which renders a label, an input field, a button and another input field (our output field). As soon as the user clicks on the button, the javascript function greet() is called. It simply gets the value of the input field and prepares a greeting for the output field. This is an example for synchronous handling. One line of code is executed after the other and there are no delays in time.

Normally web applications aren’t as simple as that. The data that is displayed is not stored inside the HTML or the Javascript and user inputs are not completely handled inside the application. Usually a server provides the necessary data for the application.

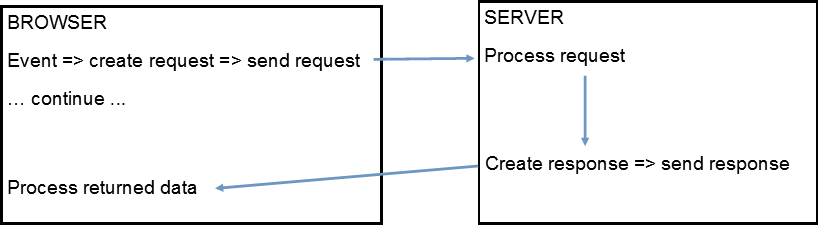

The above images shows a typical flow of a request. The user submits a form or clicks on a button in order to some information or data. An event occurs and a request is created and send with JavaScript. The server receives the request, processes it and creates and send a response. The browser receives the response and processes the data. It will take some time to deliver the request, for the server to prepare the response and to deliver the response. How long it’s going to be, is not clear by the time the browser sends the request. With synchronous handling as our fist example, the browser will stop until the request is back and the user is unable to do something else. Since no one would like to use an application like that, we work with asynchronous handling. By the time the request is send, the browser continues with the execution of script and handles other events, but once the response arrives it will continue to process the returned data.

Callbacks

To catch the arriving response callbacks are used. The next example displays a simple implementation of a XMLHttpRequest’s callback:

<div>

<input type="button" value="load Data" onClick="loadData()">

<div id="demo"></div>

</div>

function loadData() {

var xhttp = new XMLHttpRequest();

xhttp.onreadystatechange = function(){

if (this.readyState == 4 && this.status == 200) {

processData(this);

}

};

xhttp.open("GET","URL",true);

xhttp.send();

}

function processData(that) {

var response = JSON.parse(that.responseText);

var txt = "<ul>"

for (i in response.ProductCollection) {

txt += "<li>" + response.ProductCollection[i].ProductId + " - "

+ response.ProductCollection[i].Category + "</li>";

//Create corresponding request here

}

txt += "</ul>"

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = txt;

}

Once the button is clicked, a request is send to the URL in order to get data. By the time the request is finished and the response is ready (state = 4) as well as the status is ok (200), the data will be processed. In this example the response text will be parsed into a JSON object and the items will be display as a list.

Callbacks are quite handy but can be confusing when the application has a lot of requests and they are nested. For example you load a list of books and each book has a picture and comments, from people who read it already, which you want to display as well. So within the callback of the list you need to create a request go get the comments.

Promises

Alternatively you can use Promises. A promise represents a value which is not present by the time the promise is created. A request is handled asynchronous but returns a value like a synchronous function. Let’s take a look at the syntax:

var myPromise = new Promise(function(resolve, reject) {

...

});

The function body is executed immediately by the implementation of the promise. Resolve and reject ar passed into the function and called when the purpose of the function is either fulfilled or failed. A promise has three states and is always in one of them:

- pending: initial state

- fulfilled: the operation is completed successfully

- rejected: the operation has failed

At some point the promise will change it’s status to fulfilled or rejected and by that time the associated handlers queued up by the promise’s then method will be called.

The next example shows a simple implementation of a promise:

function loadData(){

var myPromise = createPromise();

myPromise.then((that) => {var response = JSON.parse(that.responseText);

//render content and create corresponding request here})

.catch((err) => console.log("rejected:", err));

}

function createPromise(){

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

var xhttp = new XMLHttpRequest();

xhttp.open("GET","URL",true);

xhttp.onreadystatechange = function(){

if (this.readyState == 4 && this.status == 200) {

resolve (this);

}else if (this.readyState == 4 && this.status !== 200){

reject(false);

}

};

xhttp.send();

})

}

By the time the request is finished and valid, then the response will be rendered. The methods then and catch return a promise as well, so they can be chained:

But why use promises instead of callbacks? This is example is really simple, but still a promise is much easier to read due to the syntactic sugar then and catch.

Let’s leave the world of web programming and look into another topic:

functional programming with JavaScript

What is functional programming? In short, functional programming is programming without mutable variables and assignments as well as imperative control flows. That means variables are constant, once a value is assigned to them, it won’t change.

For example, we want to program a light switcher. We have a light which is on or off. First approach could be something like that:

var light = {

on : false

};

function switchLight(){

light.on = !light.on;

}

switchLight();

There is a light object with on as key and true or false as value. When we want to switch the light, we change the property of the light. Thinking of functional programming, that is not what we want. We want the property of the light to be constant, so therefore we try again:

var switchedOffLight = {

on : false

};

function switchLight(light){

return { on: !light.on };

}

var switchedOnLight = switchLight(switchedOffLight);

Now the light is switched off and when we want it to be switched on, we pass the light as argument to the switchLight function. The switchedOffLight won’t change and the function only uses variables which are passed as parameter and returns a new light.

For JavaScript Arrays there are functional programmed functions like

- map

- filter

- reduce

var values = [1, 2, 3, 4];

var multiplied = values.map(function multiplyBy2(value){

return value * 2;

});

//multiplied [2, 4, 6, 8]

var reduced = values.reduce(function(accumulator, currentValue) {

return accumulator + currentValue;

});

//reduced 10

var filtered = values.filter(value => value % 2 === 0);

//filtered [2, 4]

2. What is Reactive Programming

Reactive Programming is a programming paradigm for asynchronous propagation of change - it’s often described as “event driven programming”. Instead of “execute function B after function A” or “execute function A after 5 seconds” you declare “execute function A whenever event X happens”. This is already common practice in almost every UI framework where you write event handler. You attach a function to a “button clicked” event for example. But reactive programming takes it even further by making streams of not only events but any data. And with a much more advanced API to manipulate and combine these streams.

A great embodiment of reactive programming is ReactiveX - a language agnostic specification for reactive programming libraries. We will focus mainly on ReactiveX and RxJS (the JavaScript implementation of ReactiveX) but will also show you a bit of Socket.io.

“ReactiveX is a library for composing asynchronous and event-based programs by using observable sequences.” ReactiveX

What does that mean? Instead of working directly with your data T you access them with a Observable

Observables fill the gap by being the ideal way to access asynchronous sequences of multiple items ReactiveX

| type of execution | single items | multiple items |

|---|---|---|

| synchronous | T getData() | Iterable |

| asynchronous | Future |

Observable |

This table provides an overview of the different ways to get data. We already talked about T getData() e.g. an Object, Iterable

The key elements of ReactiveX are:

- streams

- observables

- operators

- single

- subject

- schedulers

Streams From now on every input, properties, arrays are managed as part of a stream.

------------------------------------------------------------->

A stream is represented through an

Observable

An observer subscribes to an observable so when from time to time the observable emits a new item, the observer can react on that.

The following image by ReactiveX shows the flow of items emitted by an observable and processed into a new observable.

In short: an observable is a source of items which can be subscribed to. There are 3 types of output:

- onNext -> a next item

- onError -> an error occurred the stream ends

- onCompleted -> the stream ended

Operators

Operators are functions that can be called on an observable. They transform, combine or otherwise operate with the items and usually return a new observable. Be aware - like in functional programming the original values or streams won’t change and new ones are created during the operation. Since operator can return observables it’s possible to chain multiple operators. There are different types of operators:

- creating observables - operators originate new observables

- transforming observables - operators that transform items

- filtering observables - operators that only emits items matching a criteria

- combining observables - operators which combine different observables into a single one

- and many more

Single

A single is a special observable. It doesn’t emit a series of items but either emits on item or an error notification.

Subject

A subject is both observer and observable. It can subscribe to an observable and can pass through items it observes as well as emit new items.

Schedulers

With schedulers you can introduce multithreading into your observable operators, you can do so by telling those operators to use a particular scheduler.

Before we dive into the world of programming with RxJS, let’s take a look at the bigger picture. Reactive is not just a programming paradigm but also an approach to describe modern system architectures.

The reactive manifesto

Nowadays systems must be robust and flexible to fulfil the modern requirements. In times when applications are deployed on various platforms and devices such as mobile devices or even cloud-based clusters with thousands of multi-core processors and where users don’t tolerate downtime or response time above milliseconds - the requirements for software architectures are changing. Jonas Bonér, Dave Farley, Roland Kuhn, and Martin Thompson describe a system architecture which meet those requirements in their so called Reactive Manifesto. They, as well as over 20.000 supporter, say that systems which are Responsive, Resilient, Elastic and Message Driven supplies the necessary characteristics. These Systems are called Reactive Systems. When building a reactive system one gets a system which is more flexible, loosely-coupled and scalable. Therefore it is easier to develop them and they are more amenable to changes. These systems are a lot more tolerant of failure. Due to their responsiveness, they provide effective interactive feedback for users. The following graphic shows the 4 key

Now let’s take a closer look into those characteristics.

- Responsive - if a response is possible it will be within a timely manner. The focus is to provide fast and consistent response time and to build reliable upper bounds for a consistent quality of service.

- Resilient - if a failure occurs, the system remains responsive. Due to delegation, isolation, replication and containment a system can achieve resilience. In case of failure only the component in which it occurred is affected. The rest of the system stays intact.

- Elastic - the workload may vary, still the system is responsive. The system increase or decreases the resources assigned to handle the streams as reaction to changes.

- Message Driven - asynchronous messages are passed through the system. This forms boundaries between components, that provides isolation, loose coupling and location transparency.

This architecture is already very common in large system. Being aware of these principles you can apply them when designing new systems, right from the start, rather then to rediscover them during implementation.

Reactive Programming in JavaScript

Double Clicks

So what does reactive Programming look like in JavaScript? Let’s start with something common: double clicks. Lot’s of applications use them. How would you do it with traditional programming? Saving the time of every click and when another click occurs compare the current time to the previous time? But what if you want to react to single clicks and double clicks. After every single click you would need to wait a few milliseconds to see if another click has occurred. It’s obviously possible but it’s going to be some ugly code. With streams this can be done with a few simple and easy to read operations.

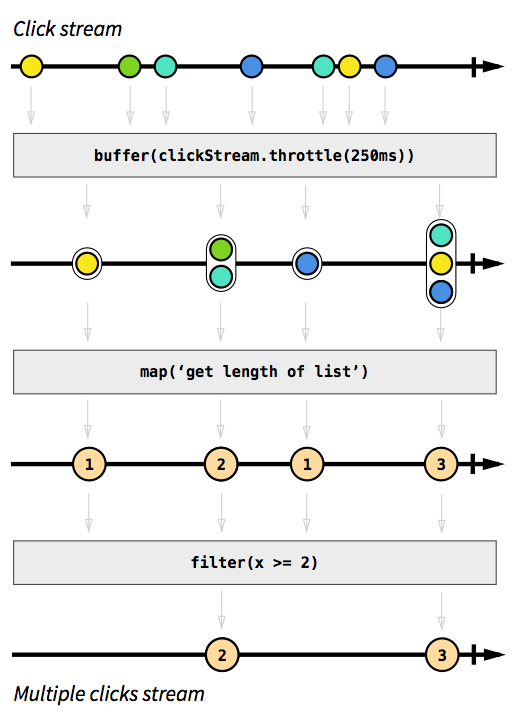

Every browser offers event handlers for button clicks. We can create a stream of click events from that button with only 1 line (and the RxJS library). At first we would want to group clicks by proximity in time. We want to group all clicks that are within 250ms of each other. Then map this list to the number of clicks in the list. So a single click within our specified 250ms will becomes a 1, double clicks a 2, triple click a 3 and so on. Then simply filter the stream to only return values equal to or greater than 2 and you have a stream that only contains events where the user clicks more than once in quick succession. This is what the streams for our double click detection would look like:

Image Source

Image Source

And this is how the code looks

const button = document.getElementById('multiclickButton');

const clickStream = Rx.Observable.fromEvent(button, 'click');

const multiClicks = clickStream

.buffer(clickStream.debounce(250))

.map(x => x.length)

.filter(x => x>=2);

multiClicks.subscribe(clicks => console.log('You made ${clicks} clicks!'))

Pretty neat, right?

First we get a reference to the button and then use RxJS to create a Observable for the click events.

Then the magic happens in just 3 lines. Buffer, map and filter.

For different buffer strategies check out the official documentation

Autocomplete

Let’s look at another example that is perfect for reactive programming: Autocomplete functionality. You type and you get suggestions in real time about what you might be typing. Let’s start of naively and work out the errors until we arrive at a working solution. We want to do something like this:

Rx.Observable.fromEvent(myInputField, 'input')

.map(searchWikipedia)

.subscribe(renderData, renderError);

function searchWikipedia(searchTerm) { /* ... */} // returns a promise

function renderData(data) { /* ... */}

function renderError(error) { /* ... */}

We get a stream from the users input in our myInputField, make a call to the wikipedia server and then render the results beneath the input field.

Why won’t this work? Well first of all the “fromEvent” functions creates a stream of events. We need the input as a string, so we add a

.map(event => event.target.value)

Now the searchWikipedia function receives proper string input. But there will probably be an error in our renderData function now. We would expect a list of suggestions or something similar, but what we end up with is a Promise! Why is that? searchWikipedia makes an HTTP call and returns a promise synchronously. So our .map(searchWikipedia) function will create a new stream filled with promises. That’s not what we want! We want a stream that emits the results of the HTTP call. That’s what the flatMapLatest is for. This will “unpack” our promises and create a stream that only emits the values once the promises have been fullfilled.

Rx.Observable.fromEvent(myInputField, 'input')

.map(event => event.target.value)

.flatMapLatest(searchWikipedia)

.subscribe(renderData, renderError);

function searchWikipedia(searchTerm) { /* ... */} // returns a promise

function renderData(data) { /* ... */}

function renderError(error) { /* ... */}

But we’re not done yet. We should only suggest something to the user if there is at least some input. A search of 1 or 2 characters is pretty pointless since the user could be writing anything when all we have is the input “A”. So let’s filter out these kinds of things.

And if a user types really really fast we will send A LOT of requests. Basically every keystroke creates a new requests. It’s probably enough to only check ever half second or so. This way our system is still suggesting ing “real time” without going overboard on HTTP requests. This can easily accomplished by throttling the stream.

.filter(input => input.length > 2)

.throttle(500)

This will leave us with this:

Rx.Observable.fromEvent(myInputField, 'input')

.map(event => event.target.value)

.filter(input => input.length > 2)

.throttle(500)

.flatMapLatest(searchWikipedia)

.subscribe(renderData, renderError);

function searchWikipedia(searchTerm) { /* ... */} // returns a promise

function renderData(data) { /* ... */}

function renderError(error) { /* ... */}

This code will query the wikipedia server every time the user enters something with 3 or more characters (but not send more than 1 requests per .5 seconds) and show the suggestions to the user. All that’s left to do is clean up. Instead of having one long chain of inputs we break it apart to make it more readable.

const rawInput = Rx.Observable.fromEvent(myInputField, 'input')

.map(e => e.target.value);

const newSearchTerm = rawInput.filter(text => text.length > 2)

.throttle(500);

newSearchTerm.flatMapLatest(searchWikipedia)

.subscribe(renderData, renderError);

function searchWikipedia(searchTerm) { /* ... */} // returns a promise

function renderData(data) { /* ... */}

function renderError(error) { /* ... */}

Observable as core data structure

In case you’re not familiar with UI development, let me tell you something: Keeping everybody up to date is a huge problem. Or rather: was a huge problem. What’s the issue? Your application has a proper dependency structure and good data flow. The services on top get data from servers. The UI components down below get services injected and get all of their data from them. The services don’t know the UI components and the UI components don’t know each other.

Let’s say you have a TweetDisplayer component. It gets a reference to the TweetService via your dependency injection and then calls the getNewTweets function of the service to fetch the newest tweets. If you press the “update” button in the TweetDisplayer it will call getNewTweets again and receive a promise. When the promise is fulfilled it will display the new tweets.

What if there is another component now: The CategoryPicker. A UI component that let’s you decided you only want to see tweets about “JavaScript”, “Cats” or some other topic. The TweetDisplayer and the CategoryPicker don’t know each other - and they shouldn’t. One should work without the other. So what happens when the CategoryPicker tells the TweetService to getNewTweets? It will receive a promise and once that promise is fulfilled the tweets are here. Here in the CategoryPicker. The TweetDisplayer was never involved and has no idea that th CategoryPicker chose a category or that the TweetService fetched new tweets! So what do you do?

Use observables!

Instead of returning one promise to the one component that called for a tweet update your TweetService will now offer a getTweetObservable function. This will return the observable that will deliver our tweets to the UI components. And unlike previously every UI component will receive the same observable! What happens when you want the service to get new tweets? First of all, the getNewTweets function will no longer return a promise. In fact it doesn’t need to do anything! Why? Because everybody that wants the newest tweets is already subscribed to the tweet observable. When the service receives new tweets it will simply publish them via the observable and everybody who subscribed will be updated. It doesn’t matter who, when or why called for new tweets, the observable delivers the newest, freshest and hottest tweets to every component in your application!

This is especially useful if you need to display the same data in multiple locations. As long as every component is subscribed to the same observable they will always have the same data!

Socket.io

Lastly I want to show you something other than RxJS because while it is a great library it’s not the only way to program reactively.

So far all of our reactions and events where user based. Button clicks, text input and so on. But what about the other side - the server.

There many use cases where a client would want to react to events from a server. The first thing that springs to my mind is a chat room.

While REST interfaces are really good for a lot of applications it’s not useful for a real time chat. You don’t want to GET /chatroom/messages every seconds and see if there are new messages. Wouldn’t it be nice if the server could just tell us when there are new messages?

Well guess what - the server CAN do that!

It’s called websockets and I’m not going into the technical details. Let’s just say it’s like an open channel between two applications where both can send messages through the channel. The perfect setup for reactive programming!

We can easily use this technology with the Socket.io library.

Note: To run this example at home you need Node.js and NPM but you can understand the code without it.

We need some libraries to set up a working web server (that’s what the first three and very last line do) and then we’re ready to programm reactively.

const app = require('express')();

const http = require('http').Server(app);

const io = require('socket.io')(http);

// Our code will go here

http.listen(3000)

We will be handling our application io which contains all current connections and we will work with sockets which are the single connections. They offer us on and emit functions and work like this:

myConnection.on(

// The name of the event - some (like "connection") are predefined, but otherwise these are our own names

'my event',

// a function that receives the data of the event

(data) => {

// do something with the data

}

);

myConnection.emit(

// The name of the event

'my event',

// The data for the event - this will be (de-)serialized with JSON so make sure that's ok for your data

someData

)

Let’s make a chat server! Start by installing the dependencies (npm i --save express socket.io) and setup yourFile.js with the stub from above. Then we implement the predefined “connection” event that will pass a socket into our fuction. In there we can declare all kinds of reactions to events. Like the ‘chat message’ event. When the socket sends us a “chat message” event, we simply emit it to every current socket (because we used io.emit - had we wrote socket.emit we would send the message only back to the sender. Remember: The socket is a single connection to a single other application).

const app = require('express')();

const http = require('http').Server(app);

const io = require('socket.io')(http);

io.on('connection', function (socket) {

socket.on('chat message', function (msg) {

io.emit('chat message', message);

});

});

http.listen(3000);

Now start the file with node (node yourFile.js in your console of choice) and the server is up and running!

And our client could look something like this:

const socket = io.connect(

'http://localhost:3000',

{ transports: ['websocket']}

);

socket.on('chat message', renderMessage);

function renderMessage(message) { /* ... */}

We connect to the localhost on port 3000 (as we defined in our server code) and choose websockets instead of polling.

Then we can just like on the server side react to events with .on and emit events with .emit

Go check out the plunker to use as a chat client (and our server code). There’s also code examples of what we talked about here, some basic exercises and one advanced exercise (Typing of the Dead):

http://embed.plnkr.co/4GeB5mRIIskWgqj75QPq/